“This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he cannot possibly save it afterward.”

This was the pledge of a dejected President.

Abraham Lincoln had had a difficult first term in office – and difficult was putting it mildly. His Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant had been fighting the ‘Overland Campaign’ against the Confederacy for months, losses had been heavy on both sides and eventually it ended only in a stalemate.

What resulted from the reaction to this result was Lincoln’s pledge above; written confidentially and signed, once sealed, by a Cabinet who had no knowledge of its contents. The stakes were unbelievably high, and the President was less than confident about being given the mandate to continue in office after a mixed bag of results in the American Civil War.

Aside from this however, Lincoln had constructed an effective anti-slavery government, through the appointment of five judges to the Supreme Court (one being his close friend and 1860 campaign manager David Davis) and the announcement of the ‘Emancipation Proclamation’ – declaring all slaves free, which he would then begin lobbying Congress to adopt via a constitutional amendment. Nevertheless, some Republicans were concerned that Lincoln was ineffectual and undeserving of renomination; when these criticisms fell on deaf ears, the most outspoken Republicans left the party and formed the Radical Democracy Party.

For a moment, it looked like once again, it would be a multi-party fight for the White House…

The Republicans

The Radical Democracy Party nominated 1856 Republican Nominee John C. Frémont for President in the hope that such a move would catalyse the Republicans to dump Lincoln and choose somebody else – in hindsight, this was probably naive of them. The President was still hugely popular amongst the main bulk of the party and, realistically, the chances of his renomination was always high.

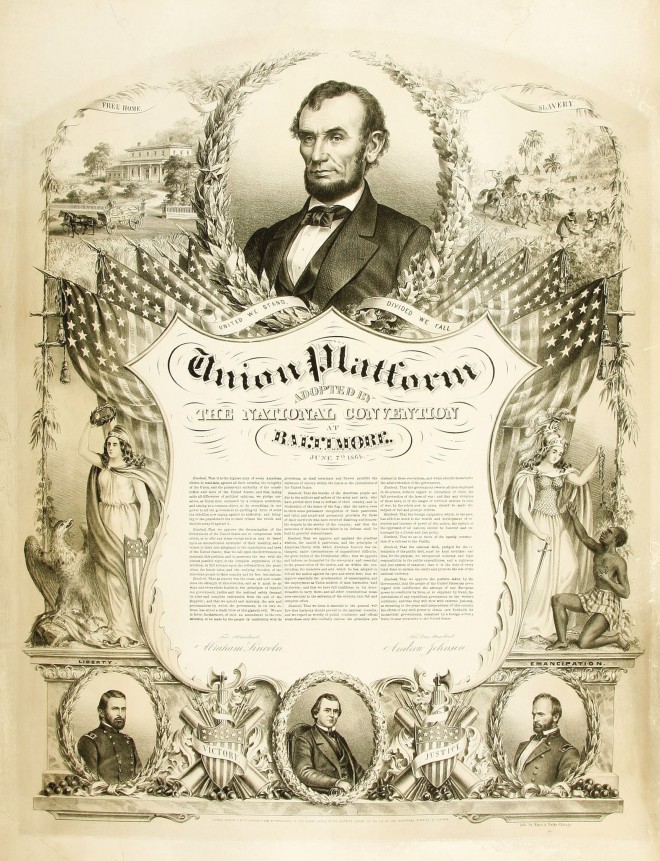

Entering the 1864 Republican National Convention held in Baltimore between the 7th and the 8th June, the main order of business was not the nomination but instead the drafting of the election platform. To begin with, the Convention decided that to guarantee re-election they had to branch their appeal beyond the traditional Republican base that, although successful in electing Lincoln in 1860, had only amounted to 39.8% of the voters four years previously. So, in order to encompass those from the Democratic Party known as ‘War Democrats’ (named as such because they endorsed Lincoln’s attitudes towards the war compared to ‘Peace Democrats’ who insisted on an immediate peace settlement with the Confederacy), the Republican Party was changed to the National Union Party – stressing the central theme of the election: Uniting the Nation.

The National Union platform that followed was summed up in eleven key points:

- Resolution One focussed on the unity of purpose that held the party together, and underlying said purpose, stating: “…laying aside all differences of political opinion, we pledge ourselves, as Union men, animated by a common sentiment and aiming at a common object, to do everything in our power to aid the Government in quelling by force of arms the Rebellion now raging against its authority, and in bringing to the punishment due to their crimes the Rebels and traitors arrayed against it.”

- Resolution Two was charged with the mandate given to the government in regard to the Civil War: “…we approve the determination of the Government of the United States not to compromise with Rebels, or to offer them any terms of peace, except such as may be based upon an unconditional surrender of their hostility and a return to their just allegiance to the Constitution and laws of the United States, and that we call upon the Government to maintain this position, and to prosecute the war with the utmost possible vigor to the complete suppression of the Rebellion…”

- Resolution Three followed on from its predecessor in outlining the aim of both the ‘rebels’ of the Confederacy, and the conclusive aim of the Union: “…Slavery was the cause, and now constitutes the strength, of this Rebellion, and as it must be, always and everywhere, hostile to the principles of Republican Government, justice and the National safety demand its utter and complete extirpation from the soil of the Republic…”

- Resolution Four turned attention towards the immense human cost of the Civil War, both in loss of life and in life-changing injuries: “…the thanks of the American people are due to the soldiers and sailors of the Army and Navy, who have periled their lives in defence of their country and in vindication of the honor of its flag; that the nation owes to them some permanent recognition of their patriotism and their valor, and ample and permanent provision for those of their survivors who have received disabling and honorable wounds in the service of the country; and that the memories of those who have fallen in its defence shall be held in grateful and everlasting remembrance…”

- Resolution Five saw the endorsement of Lincoln’s governance: “…we approve and applaud the practical wisdom, the unselfish patriotism and the unswerving fidelity to the Constitution and the principles of American liberty, with which Abraham Lincoln has discharged, under circumstances of unparalleled difficulty, the great duties and responsibilities of the Presidential office…”

- Resolution Six continued on this theme, extending gratitude to the officials within Lincoln’s administration, as the Convention inferred that they would follow the resolutions passed religiously: “…we regard as worthy of public confidence and official trust those only who cordially endorse the principles proclaimed in these resolutions, and which should characterize the administration of the Government…”

- Resolution Seven sought to underline legal protections for the Union Army: “…the Government owes to all men employed in its armies, without regard to distinction of color, the full protection of the laws of war…”

- Resolution Eight acknowledged the need for a revised immigration law: “…foreign immigration, which in the past has added so much to the wealth, development of resources and increase of power to this nation, the asylum of the oppressed of all nations, should be fostered and encouraged by a liberal and just policy…”

- Resolution Nine reaffirmed an earlier Republican commitment: “…we are in favor of the speedy construction of the Railroad to the Pacific coast…”

- Resolution Ten was focussed on the economy: “…the National faith, pledged for the redemption of the public debt, must be kept inviolate, and that for this purpose we recommend economy and rigid responsibility in the public expenditures, and a vigorous and just system of taxation; and that it is the duty of every loyal State to sustain the credit and promote the use of the National currency…”

- The eleventh and final Resolution outlined the defence against international interference with the War or the Government “…we approve the position taken by the Government that the people of the United States can never regard with indifference the attempt of any European Power to overthrow by force or to supplant by fraud the institutions of any Republican Government on the Western Continent…”

There were *technically* two candidates for the Republican nomination, although only Lincoln declared his interest while Grant was unwittingly drafted by the Missouri delegation:

- Abraham Lincoln, incumbent President of the United States

- Ulysses S. Grant, Commanding General of the United States Army

On the first ballot only Missouri’s 22 delegates voted for Grant, leaving Lincoln with 494 votes – when the ballot was revised, Missouri flipped to Lincoln to give him a unanimous renomination.

Vice President Hannibal Hamlin however, was not as safe. He was associated with the ‘radicals’ who had splintered off and formed the Radical Democracy Party, and Lincoln used the re-branded designation of his party to replace Hamlin with a new running mate. The Military Governor of Tennessee and former Senator Andrew Johnson was chosen as Hamlin’s replacement; a Democrat, it was hoped that Johnson’s presence on the ticket would help win over wavering War Democrats.

Lincoln, who did not attend the Convention personally (which was customary at the time), wrote to the Convention after his renomination and gave the following address:

“I am very grateful for the renewed confidence which has been accorded to me, both by the convention and by the National League. I am not insensible at all to the personal compliment there is in this; yet I do not allow myself to believe that any but a small portion of it is to be appropriated as a personal compliment. The convention and the nation, I am assured, are alike animated by a higher view of the interests of the country for the present and the great future, and that part I am entitled to appropriate as a compliment is only that part which I may lay hold of as being the opinion of the convention and of the League, that I am not entirely unworthy to be instructed with the place I have occupied for the last three years. I have not permitted myself, gentlemen, to conclude that I am the best man in the country; but I am reminded, in this connection, of a story of an old Dutch farmer, who remarked to a companion once that “it was not best to swap horses when crossing streams.”“

As such, Lincoln and Johnson departed the Convention as the only cross-party national ticket in election history…

The Democrats

The 4th Commanding General of the US Army George B. McClellan who had led the Union Army in 1861 throughout the Peninsula Campaign – the first major offensive campaign undertaken against the Confederacy. Although initially it seemed McClellan would be successful through his unorthodox tactics of encircling the enemy, soon the Confederate Army had the upper hand and the campaign ended in a Union defeat.

Resultantly, Lincoln and McClellan grew to dislike one another. Eventually, in November 1862, the President had McClellan dismissed. The importance of this, although nothing too out of the ordinary at the time, would only be realised later on…

Like in 1860, the Democrats were bitterly split in 1864. War Democrats were divided from Peace Democrats, who were equally as divided from ‘Copperheads’ – these were Peace Democrats who had lost all faith in the war effort, and demanded an immediate end to hostilities with the South, without acknowledging a Union victory.

The Convention’s first day, held in Chicago, on the 29th August 1864 adopted a platform adhering the policies of Peace Democrats. This was a platform that went against the policies of the War Democrat frontrunner for the nomination. The frontrunner? Former General George B. McClellan. He was a man dedicated to the War and restoring the Union, not placating the South.

Three candidates were placed into nomination at the start of balloting for the 1864 Democratic nomination:

- George B. McClellan, former General from New Jersey – a War Democrat

- Thomas H. Seymour, former Minister to Russia and former Governor of Connecticut – a ‘Copperhead’

- Horatio Seymour, former Governor of New York

Horatio Seymour’s colleagues had entered his name into consideration without his approval and, once the former Governor got wind of the move, he made it perfectly clear that he was not after the nomination and would not accept it either. There were even rumblings that former President Franklin Pierce would be placed into contention, but he too refused to be considered.

McClellan won almost unanimously on the first ballot. Whilst the Presidential nomination was pretty much a sealed deal, the spot of Vice Presidential candidate was much more contested; a total of eight candidates were placed into consideration.

These candidates were:

- George H. Pendleton, a Representative from Ohio

- James Guthrie, the former Secretary of the Treasury from Kentucky

- Lazarus W. Powell, the Senator from Kentucky

- George W. Cass, the Railroad President from Pennsylvania

- John D. Caton, former Chief Justice of the Illinois Supreme Court

- Daniel W. Voorhees, a Representative from Indiana

- Augustus C. Dodge, former Senator from Iowa

- John S. Phelps, a former Representative from Missouri

Before the first ballot’s votes could be finalised, Guthrie, Powell, Caton and Phelps (who had come in first, third, fifth and eighth during the roll-call) all made it known they did not wish to be nominated. Subsequently, around 70 delegates from the withdrawn candidates corrected their votes and sent them towards Pendleton, a man close to senior Copperheads, who was able to clinch the Vice Presidential nomination.

Although Pendleton’s stance on the Civil War subsequently differed hugely from McClellan at the top of the ticket, the nomination of them both together helped balance out the platform and unite the party around them both.

The Campaign

After three years of war, and various stalemates, the Lincoln campaign were concerned that the Copperhead message of peace at all cost would cut through to voters, and that the presence of Frémont on the ballots across the nation would split the pro-Union vote and see a McClellan victory – even with only a plurality of the popular vote.

However, whilst the Democratic National Convention had tried hard to unify its party, it also inadvertently succeeded in unifying the Republicans too. Frémont was disgusted by the Democratic platform, believing it to be a regressive movement back to a co-existence with slavery which was anything but acceptable. By September 1864, Frémont decided that, although Lincoln had not done enough as President, the Union and fight against slavery was of paramount importance and therefore he was exiting the race – most importantly he was also endorsing Lincoln’s ticket in November. Defeating McClellan was now the priority amongst Republicans and, thanks to the presence of Andrew Johnson on President Lincoln’s ticket, many War Democrats. Indeed, their slogan of “Don’t Change Horses in the Middle of a Stream” captures the necessity of a Lincoln victory in November.

Also in September, Union forces led by William Tecumseh Sherman precipitated the fall of the city of Atlanta, a key Confederate stronghold, on the 2nd – allowing for a clear route for a Union victory in the very near future. Suddenly, there seemed no need to settle for peace at all costs, if a winner takes all victory tinted with glory was just around the corner.

With the departure of Frémont and the fall of Atlanta, McClellan’s hopes of beating the President in November were pretty much dead in the water.

Results

Lincoln scored a convincing victory on the 8th November, including narrow wins in key swing states like New York and Pennsylvania, alongside wins in states that voted for Stephen A. Douglas and John C. Breckinridge in 1860; these were Missouri and Mississippi. The President also won the three newly admitted states of Kansas, Nevada and West Virginia. Unlike in 1860, Lincoln also won the popular vote by a ten point margin: 55% to 45%.

McClellan only succeeded in carrying three states, including his home state of New Jersey, which amounted to just 21 electoral votes against Lincoln’s 212. Hugely, of all ballots cast by serving army members, Lincoln took over three quarters into his final totals, with McClellan only winning 22.9% of this particular vote.

| Candidate | Home State | Electoral Vote (118 to win) | Popular Vote |

| ABRAHAM LINCOLN Republican | IL | 212 | 2,218,388; 55.0% |

| GEORGE B. McCLELLAN Democratic | NJ | 21 |

1,812,807; 45.0% |

| ELLSWORTH CHEESEBOROUGH Independent | KS | 0 | 543;0.01% |

Elections were held in the Union-held territories of Louisiana and Tennessee (recently liberated from the Confederacy) but as they had not been officially readmitted to the Union their electoral votes, both states having gone for Lincoln, were not officially counted; had they been, Lincoln would have won an even bigger majoruty of 229 electoral votes.

Aftermath

Lincoln’s second inauguration (the first President to have such an event since Andrew Jackson in 1833) took place on March 4th 1865. His remarks on the Civil War became infamous and are now featured on the Lincoln Memorial; he said:

“Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s 250 years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said 3,000 years ago, so still it must be said, “the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether”. With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.“

On April 9th 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant, effectively ending the American Civil War. It was not long until the Confederacy collapsed completely.

The end of the Civil War and the Union victory angered many Southern sympathisers in the North including famous actor John Wilkes Booth, who hatched a plan with some of his closest friends to kidnap the President to blackmail the North into releasing Southern prisoners – but the logistics of this saw the plan fall through fairly quickly. Nevertheless, Booth was determined to avenge the South.

On April 14th, Booth trudged to Ford’s Theatre in Washington D.C. to collect his post when he found out that both President Lincoln and General Grant would be in attendance later to watch a performance of Our American Cousin. This gave Booth the opportunity he had been looking for. By 7pm that evening he had assembled his friends to assign them roles going forward:

- Lewis Powell would assassinate William H. Seward, the Secretary of State, at his D.C. residence

- George Atzerodt was tasked with killing Andrew Johnson, the new Vice President, who was staying at the Kirkwood Hotel

- Booth himself would kill Lincoln and Grant at the theatre

It was a bold plan to say the least, but Booth’s burning desire to avenge the loss of the Confederacy in the Civil War drove it further.

The beginning of the cracks in Booth’s plan was completely out of his control – Mary Lincoln and Julia Grant were not particularly friendly with one another at this moment in time and therefore General Grant declined the President’s invitation to Ford’s Theatre that evening.

The President and the First Lady arrived, slightly late, to Ford’s Theatre and settled into the specially prepared Presidential Box before the audience rose and ‘Hail to the Chief’ was played, in honour of their esteemed guest. A local policeman, John Frederick Parker, was assigned to guard the Lincoln’s, but he left them during the intermission to join the President’s valet at a nearby tavern. It was within this margin of opportunity that Booth entered the box where they were sitting. Booth knew the play off by heart and waited for an especially humorous line to time his attack – the line “Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal; you sockdologizing old man-trap!” As Lincoln laughed at this, Booth stepped forward, aimed his pistol and shot the President from behind; the bullet entered his head behind the left ear, passing through the brain and ended up near the front of his skull.

The assassin leapt from the box onto the stage and then took off into the night.

The President, unconscious but still breathing, was moved to the house of a nearby tailor where physicians came from all around to analyse his wound – they all determined his injuries were fatal. At 7:22 am the next morning, the 56 year old President passed away. Vice President Johnson succeeded him.

Both Powell and Atzerodt failed to carry out their respective assassinations – Powell attempted to stab a bed-bound Seward, who was recovering from a broken jaw, in his home but was scared off, whilst Atzerodt got drunk instead of killing the Vice President.

Booth was eventually tracked down and killed in a gunfight with soldiers from the 16th New York Cavalry, whilst his co-conspirators were found guilty and executed.

Eerily, days before his assassination, Abraham Lincoln recalled a dream he had had that night to his bodyguard. Apparently, according to his bodyguard’s recollection, Lincoln had heard mournful cries in his dream so set off after them:

“I kept on until I arrived at the East Room, which I entered. There I met with a sickening surprise. Before me was a catafalque, on which rested a corpse wrapped in funeral vestments. Around it were stationed soldiers who were acting as guards; and there was a throng of people, gazing mournfully upon the corpse, whose face was covered, others weeping pitifully. “Who is dead in the White House?” I demanded of one of the soldiers, “The President,” was his answer; “he was killed by an assassin… In this dream it was not me, but some other fellow, that was killed. It seems that this ghostly assassin tried his hand on someone else.”

President Lincoln was dead. The Civil War was over. The Reconstruction of the United States was now up to the new President Andrew Johnson – and he had one hell of a job ahead of him.